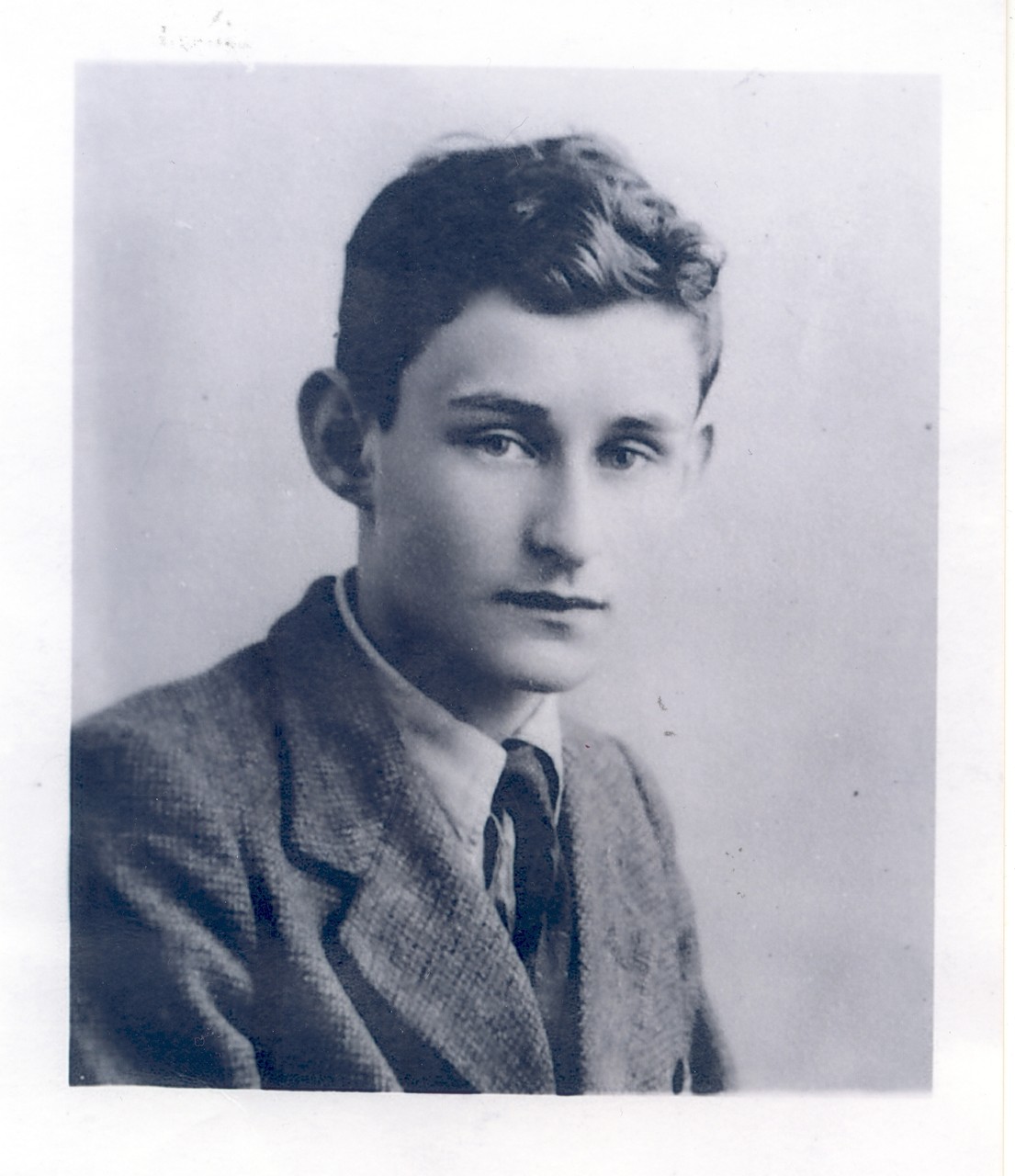

Maurice Pertschuk came from a Russian-Jewish family. He was of British nationality but was born in France, where his family had lived for a long time. Not even 20 years old, he volunteered for the British military at the beginning of the war. As he was able to speak French without an accent, the Secret Service recruited him for a new special unit, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). Their agents operated behind enemy lines and organized local resistance against the German occupying forces. After several months of training in England, he arrived in southern France by boat in April 1942. In the Toulouse area, he attempted to set up a new resistance network. The young agent acted successfully: within a short time, Maurice Pertschuk recruited a large number of French men and women in factories and public institutions. The group he led distributed leaflets, carried out sabotage actions and organized arms deliveries from England. Maurice Pertschuk was arrested in April 1943 along with other members of his resistance group. An informer had betrayed her to the Germans.

The Gestapo first imprisoned him for several months in Fresnes prison near Paris. In January 1944 he was deported to Buchenwald Concentration Camp via Compiègne police camp. His real identity and function were not clear to the Gestapo at this point. The SS in Buchenwald registered him as an English student with the name Martin Perkins, an alias used by Maurice Pertschuk. His fellow inmates later described him as a quiet, very polite and comradely young man. He worked in the camp's depot and wrote poetry. Only shortly before the liberation did the German authorities succeed in unmasking him as an agent. This was his death sentence. On March 29, 1945, the SS murdered the 23-year-old in Buchenwald. One of the last entries in his British Secret Service personnel file read: "An officer who has always been distinguished and particularly hard-working. It is a tragedy that he was executed days before liberation after surviving for so long. The more we hear about his work in Toulouse and his exemplary behavior in the camp, the more we honor his memory. A man to be proud of.” A year after the end of the war, the poems he wrote in Buchenwald entitled “Leaves of Buchenwald” were published for the first time.