On February 18, the Picasso Museum in Paris opened the exhibition, "L’art ‘dégénéré’ : Le procès de l’art moderne sous le nazisme” (“Degenerate Art”: The Trial of Modern Art under Nazism), exploring one of the most infamous cultural purges of the 20th century. The term “degenerate art” (German: Entartete Kunst) was coined by the Nazi regime to condemn modernist movements that did not conform to its ideological vision. The exhibition revisits the 1937 Munich show that sought to ridicule and banish avant-garde art while glorifying the Nazi aesthetic.

The 1937 "Degenerate Art" Exhibition: A Political Weapon

The Nazi campaign against modern art began almost immediately after Hitler’s rise to power in 1933. The regime sought to eliminate artistic movements that did not align with its ideology, favoring instead art that depicted heroic Aryan figures, nationalist themes, and rural German landscapes. Works that were abstract, experimental, or created by Jewish or leftist artists were labeled “degenerate” and purged from museums.

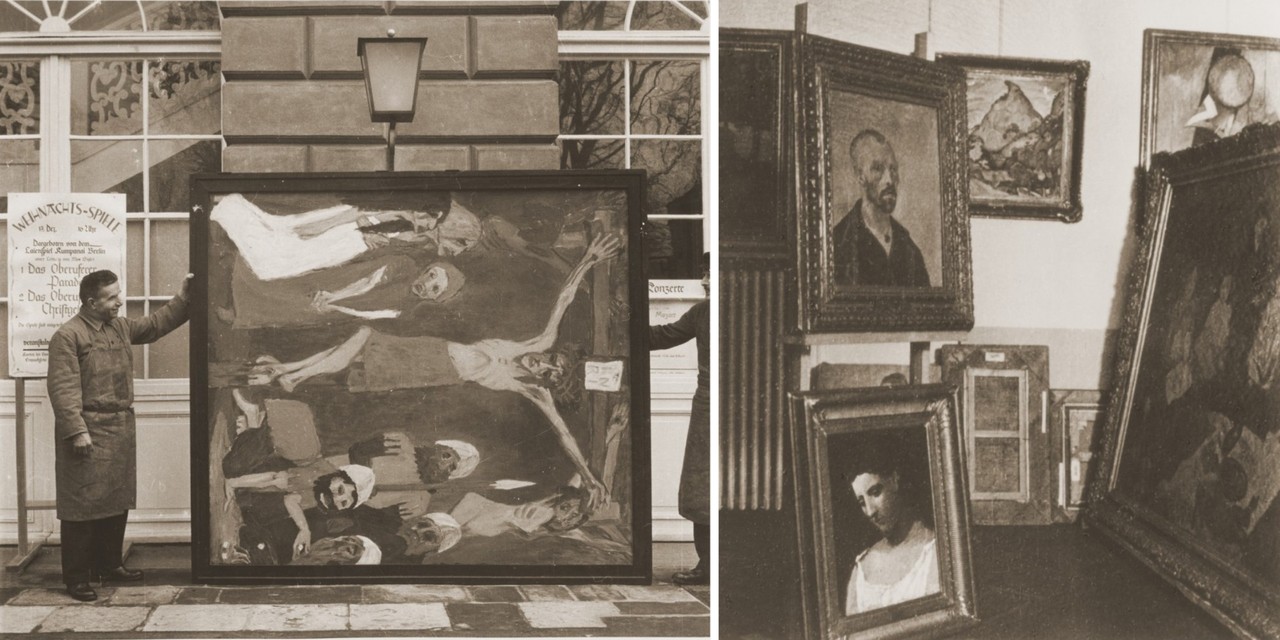

In 1937, the Nazi Ministry of Propaganda, led by Joseph Goebbels, organized the “Entartete Kunst” exhibition in Munich, displaying 700 confiscated works in a deliberately mocking presentation. Artists such as Pablo Picasso, Marc Chagall, Wassily Kandinsky, George Grosz, and Otto Dix were prominently featured, their work accompanied by demeaning captions meant to discredit modernism. Meanwhile, a parallel exhibition, "The Great German Art Exhibition," was staged to promote the state-approved, classical art style favored by the Nazis.

Despite its propagandistic purpose, the “Degenerate Art” exhibition attracted between two and three million visitors, making it one of the most attended art exhibitions of its time. What was intended as an act of condemnation inadvertently became one of the largest showcases of avant-garde art in the 1930s.

The Fate of “Degenerate Art”

The Nazis systematically removed more than 16,500 modernist artworks from German museums. Some were destroyed—over 5,000 pieces were burned in Berlin in 1939—while others were sold abroad through carefully controlled auctions. These sales were intended to generate foreign currency for the regime, though many collectors refused to participate, unwilling to financially support the Nazis.

Many artists faced persecution. Some, like Felix Nussbaum, were deported and murdered in Nazi camps. Others, such as Otto Dix and Emil Nolde, experienced professional ruin. Those who remained in Germany sometimes withdrew from public life, living in what was called “inner exile.”

While the Nazis sought to erase avant-garde art from public life, many of the artists labeled as “degenerate” went on to shape 20th-century art history. Picasso, Chagall, and Kandinsky are now considered masters of modernism, and institutions worldwide have reclaimed and restored many of the works once deemed unworthy.

A New Look at “Degenerate Art” in Paris

The Picasso Museum’s exhibition is the first large-scale presentation of this topic in France in over three decades. It benefits from new discoveries, including artworks hidden by the family of Hildebrand Gurlitt, one of the Nazi-approved art dealers, and pieces recently recovered from bombed storage sites.

One striking feature is a wall listing all artists labeled “degenerate” by the Nazis, with those included in the exhibition highlighted in black. This visual representation underscores the scale of the cultural suppression. The exhibition also examines the looting and sale of modernist works, revealing the role of art markets in Nazi economic strategies.